Newfoundland Traditions & Folklore

Jiggs Dinner

According to urban legend, there are more than a few origin stories

for the name "Jiggs Dinner". Once legend recalls the

Newfoundlanders' adoration of a kitchen party and that they all love

to dance and do a jig in the kitchen supposedly while the pot is on

the boil. Another recalls that the salt beef, the most necessary

item in the pot, was imported from New York by a company called

Jiggs. One more suggests the way you would extract those boiled

vegtables and bag of pease pudding out of the pot is reminiscent of

jigging a codfish. While the name "Jiggs Dinner" didn't come around

until the turn of the 20th. century. It's components have

long been part of the Newfoundland and Labrador culinary cannon.

The meal most typically consists of salt beef (or salt riblets), boiled

together with potatoes, carrot, cabbage, turnip, and greens. Pease pudding

and figgy duff are cooked in pudding bags immersed in the rich broth

that the meat and vegetables create. Condiments are likely to include

mustard pickles, pickled beets, cranberry sauce, butter, and a thin gravy

made from the cooking broth. The leftover vegetables from a Jiggs dinner

are often mixed into a pan and fried to make a dish known as "cabbage

hash" or "corned beef and cabbage hash", much like bubble and squeak.

Mummering

Mummering is a Christmas-time house-visiting tradition practised in

Newfoundland and Labrador, Ireland, City of Philadelphia, and parts

of the United Kingdom.

An old Christmas custom from England and Ireland, mummering in a version

of its modern form can be traced back in Newfoundland into the 19th century.

Although it is unclear precisely when this tradition was brought to Newfoundland

by the English and Irish, the earliest record dates back to 1819. Some

state that the tradition was brought to Newfoundland by Irish immigrants

from County Wexford. The tradition varied, and continues to vary, from

community to community. Some formal aspects of the tradition, such as

the mummers play, have largely died out, with the informal house-visiting

remaining the predominant form.

On June 25, 1861, an "Act to make further provisions for the prevention of Nuisances" was introduced in response to the death of Isaac Mercer in

Bay Roberts. Mercer had been murdered by a group of masked mummers

on December 28, 1860. The Bill made it illegal to wear a disguise in

public without permission of the local magistrate. Mummering in

rural communities continued despite the passage of the Bill,

although the practice did die out in larger towns and cities. In the

1980s, mummering experienced a revival, thanks to the locally

popular musical duo Simani, who wrote and recorded "Any Mummers Allowed In?" (commonly referred to as "The Mummer's Song") in 1982.

Folklorist Dr. Joy Fraser has noted that, in common with many other

folk revivals, the resurgence of Christmas mummering in Newfoundland

is largely based on a selective and idealised conceptualisation of

the custom.

As part of this revival, one particular form of mummering - the informal

house-visit described above - has come to represent the custom in Newfoundland

as a whole, while other forms that were equally prominent in the island's

cultural history have received comparatively little attention. In 2009,

the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador's Intangible Cultural

Heritage office established what would become an annual Mummers Festival,

culminating in a Mummers Parade in St. John's. The success of the festival

has influenced, in part, another revitalization and increase of interest

in the tradition in the province.

Tibs' Eve

Tibb's Eve, Tip's Eve, Tipp's Eve or Tipsy Eve are regional

variations used throughout Newfoundland and Labrador to describe the

same celebration. Eventually, proverbial explanations arose as to

when this non-existent Tibs Eve was: "Neither before nor after

Christmas" was one. "Between the old year and the new" was another.

Thus, the day became associated with the Christmas season. Sometime

around World War II, people along the south coast of Newfoundland

began to associate 23 December with the phrase 'Tibb's Eve' and

deemed it the first night during Advent when it was appropriate to

have a drink. Advent was a sober, religious time of year and

traditionally people would not drink alcohol until Christmas Day at

the earliest. Tibb's Eve emerged as an excuse to imbibe two days

earlier. For some people, Tib's Eve is the beginning of the

Christmas season.

Observed on December 23rd and sometimes called Tip's Eve or Tipsy Eve,

it's one of several extensions of the holidays. For many Newfoundlanders,

this day is the official opening of Christmas, the first chance to drink

the Christmas stash. The date of Tib's Eve is only known in Newfoundland.

The tradition of celebrating Tibb's Eve may be similar to 19th century

workers taking Saint Monday off from work.

An outport tradition not originally celebrated in St. John's, Tibb's Eve was adopted circa 2010 by local bar owners, who saw it as a business opportunity. Brewery taproom owners have suggested that hosting Tibb's Eve events allow them to open up "Newfoundland experiences to outsiders. "The informal holiday has been also used for fundraising efforts, including the "Shine Your Light on Tibb's Eve" fundraiser for the St. John's Women's Centre, first organized circa 2009 in St. John's, and Tibb's Eve charity drives organized by the Masons in Grand Bank, NL. Since then, social media and expatriate Newfoundlanders have spread the tradition to other parts of Canada, such as Halifax, Nova Scotia and Toronto, Ontario. In 2014, Grande Prairie Golf and Country Club in Alberta hosted a Newfoundland-themed Tibb's Eve event, in support of local charities. In 2016, Folly Brewpub in Toronto brewed its own "Tibb's Eve" spiced ale. In 2019, comedian Colin Hollett described the holiday this way for a Halifax "Tibb's Eve on December 23, when people drink and eat at kitchen parties and bars with all the people they want to celebrate with before spending time with those they have to. I have no idea how that isn't huge everywhere else." The concept of the day being the "official" start of the Christmas holiday season was promoted in local media by 2020. In 2021, several Newfoundland bars hosted Tibb's Eve ugly Christmas sweater events, while Port Rexton Brewery produced a "Tibbs the Saison" beer.

St. Patrick's Day

Because of the time zone, Newfoundland is the first spot in North

America to celebrate St. Patrick's Day, just a few hours after it's

officially St. Patrick's Day in Ireland. Every year, St. John's is

the first capital city in North America to officially kick off St.

Patrick's Day. If you're in North America and want to get close to

Ireland, the closest spot is in Newfoundland. St. John's Harbour is

the closest North American port to Ireland and Cape Spear is the

closest point of land, which is just a short drive from St. John's

Harbour.

Often times when people from Newfoundland travel internationally they're

mistaken for being Irish because of the way they speak. Since many parts

of Newfoundland were originally settled by people from Ireland, many

residents in Newfoundland are direct descendants of Irish immigrants,

retaining much of the same dialect and accent. Most people are wearing

green, restaurants have special menus, and St. Patrick's Day celebrations

are everywhere. In Newfoundland, St. Patrick's Day is bigger than the

Easter Bunny and more popular than Black Friday

Sheila's Brush

If you live in Newfoundland, Sheila's Brush needs zero explanation.

It is a storm, usually a big storm that occurs on or after St.

Patrick's Day. It is typically the last big storm of the season. But

who is Sheila? The term comes from an Irish legend that says that

Sheila was the wife or sister or mother of St. Patrick and that the

snow is a result of her sweeping away the old season, which is

fitting since Spring begins later the week. There is also a legend

that Sheila shows up to punish Newfoundlanders for the heavy

partying that happens on St. Patrick's Day.

Do you believe in Sheila's Brush?.....

Garden Parties and Regattas

Throughout Newfoundland, churches have held Garden Parties to raise

funds for local parishes or for special projects. On some designated

day, usually a Sunday when fewer people would be working, a day-long

party is held outdoors, if the weather is fine, or in the church

hall, if not. With wheels of fortune, and races in the afternoon,

meals served at suppertime, and a dance at night, the festivities

would continue for hours.

In recent years the organization of such community-wide parties has frequently

devolved to town councils, and a weekday often in early August has been

set aside. In some larger towns the garden party became a regatta - Harbour

Grace, Placentia and St John's are three examples. The St John's Regatta

is the largest of these garden-parties-become-regattas; on the first

Wednesday in August (or the first fine day thereafter), the city stops

working and attends the boating races on Quidi Vidi Lake. Upwards of

30,000 attend every year, with estimates in some years of over 50,000

people attending the day-long event.

Shrove Tuesday

Pancake Night, or Shrove Tuesday, is typical of Newfoundland

calendar customs. Derived from widespread customs in European

traditions, and shaped as much by religious beliefs as by

traditional divinational activities, it is a mixture of traditions,

evolving continuously. Shrove Tuesday (named for the religious

practice of confessing one's sins and being "shriven" or "shrove" by

the priest immediately before Lent began) was a time to use up as

many as possible of the foods banned during Lent: meat products in

particular, including butter and eggs.

Pancakes were a simple way to use these foods, and one that could entertain

the family. Objects with symbolic value are cooked in the pancakes, and

those who eat them, especially children, take part in a divinatory game

as part of the meal. The person who receives each item interprets the

gift according to the tradition: a coin means the person finding it will

be rich; a pencil stub means he/she will be a teacher; a holy medal means

they will join a religious order; a nail that they will be (or marry)

a carpenter, and so on.

The 'Screech-In'

Perhaps the most controversial non-calendric custom in Newfoundland

in recent years is the Screech-In. It is historically related to

such traditions as equatorial line-crossing and initiation rites

known all over the world. It derives from "honorary Newfoundlanders"

rites of the 1940s and pranks played on new sealers going to the

ice. The Screech-In came into being in the 1970s when Joe Murphy and

Joan Morrissey put together an entertainment at the Bella Vista

Country Club in St John's. It included local musical performers and

a dress-up skit by which members of the audience were humorously

"screeched-in." In later years the Screech-In was widely performed

by Myrle Vokey and by employees of the Newfoundland Liquor

Commission. Typically, initiates are made to kiss a codfish, drink

some Screech (rum) and repeat a semi-dialect, slightly risqué

recitation.

In 1990 the custom came under fire from several directions and was attacked

as a destructive mocking of Newfoundland culture. The Premier at the

time, Clyde Wells, ordered the Liquor Commission to destroy "Order of

Screechers" certificates that bore his official signature. Nonetheless,

the Screech-In has continued in the 1990s as a widely favoured way of

welcoming visitors to Newfoundland with an entertaining ritual.

Newfoundland Architecture

The unique and striking architecture of Newfoundland has served to

draw many tourists to the province. The preservation of individual

structures is crucial to the tourist industry, and the economic well

being of communities. Many people are drawn towards our beautiful

old buildings and we, as Newfoundlanders, feel a strong pride that

goes along with the wood and nails. The preservation of Newfoundland

folk architecture in recent years has received deserving attention.

In Bonavista, for example, the community college has developed a

heritage carpentry course. Students learn how to reconstruct

heritage houses, and as a result they are also enriched with the art

of making traditional furniture. In Trinity, a number of local

carpenters have revived the making of traditional windows and have

created a market for these products throughout the province. Also,

an inventory of Newfoundland folk homes is being compiled as part of

a strategy to preserve Newfoundland's architectural heritage.

A distinguishing feature of the majority of houses in Newfoundland is

their wooden construction. The reason for this goes back to the seventeenth

century. When settlers first landed on our shores they could not ignore

the abundance of lumber around them. The style at the time in Europe

was to build with lumber so these New World settlers also built their

houses of wood.Availability of wood was not the only reason why they

chose lumber as the best material. Building a stone or brick house required

a great deal of time and money, neither of which was available to most

settlers. To build a stone or brick house required special skills and

many months of dry warm weather which Newfoundland does not always enjoy.

As well, bricks had to be shipped from England in order to have them

as a building material. Stone was not an acceptable building material

either, because the settlers would have to locate and operate an accessible

quarry.

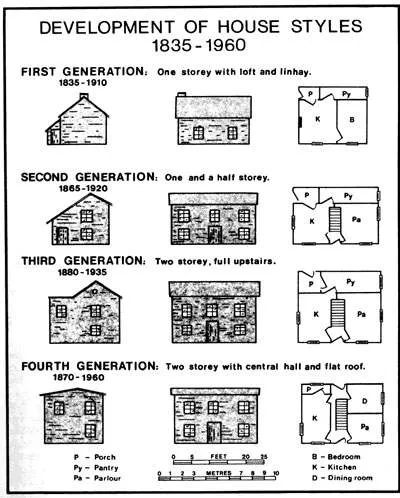

First generation homes Sometimes referred to as a settlers house, these

homes were built most frequently from 1835-1910. These houses were very

rugged looking one storey dwellings and were made from rudimentary materials.

Second generation homes Better known as a salt box, these homes were

built most frequently from 1865-1920. The house pictured below was basically

a settlers house, but was built with higher quality materials. This house,

however, had one and a half storeys. Third generation homes This house

is also known as a salt box (modified). It was built most frequently

between 1880-1935. This house had two full storeys and was slightly larger

than the salt box. Fourth generation homes This house, the largest of

the folk houses, has two full storeys, a central half hall, and a flat

roof. This house, known as a biscuit box, was built most frequently between

1870-1960.